Divya Iyer, DNA

Hang the rapists”, screamed some of the signs at the protests that followed the rape and murder last December in Delhi. Others went further, calling for castration, torture and public beheadings.

Implicit in these demands was the notion that the death penalty and other extreme punishment act as a deterrent, or serve as just retribution for horrific crimes, especially those against women.

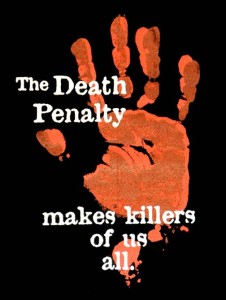

Death penalty does neither of these things. As a few women’s groups have recognised, death penalty is only a quick-fix solution; short-term revenge masquerading as justice.

For any punishment to be a true deterrent, it must be swift, certain and sufficiently severe. Potential offenders need to anticipate being identified, investigated and prosecuted before they are punished. The death penalty is clearly severe, but punishment in India is both slow and uncertain.

Some crimes against women, like marital rape, are not even considered crimes under law. Crimes like rape, sexual assault, stalking, or street harassment are frequently under-reported, for fear of stigma or reprisal. When complaints are made, they need to be converted into FIRs, following which investigations must be conducted, charges framed, and trials held and completed. At each of these stages, our largely antiquated and insensitive criminal justice system lets down survivors of sexual violence, apart from subjecting them to various indignities. In 2012, the conviction rate for rape was a dismal 24%.

In such a scenario, an extreme punishment would carry little deterrent effect.

There is no convincing evidence that the death penalty prevents crimes more effectively than other punishments. The most comprehensive survey of research findings carried out by the UN on the relationship between the death penalty and homicide concluded: “Research has failed to provide scientific proof that executions have a greater deterrent effect than life imprisonment. Such proof is unlikely to be forthcoming. The evidence as a whole still gives no positive support to the deterrent hypothesis.”

Data from countries that have abolished the death penalty show that its absence has not resulted in an increase in crime. The death penalty does not offer a transformative idea in a social context where violence against women often involves notions of izzat or honour. It does not change patriarchal attitude and feudal mindset that trivialise and condone violence against women—be it from the man on the bus or a senior politician.

The debate around the death penalty also deflects attention from the harder procedural and institutional reform that the government must bring about to tackle violence against women more effectively. The Justice Verma Committee had recommended radical reforms to police management and the ways in which crimes against women are registered and investigated. But these suggestions have not been implemented.

The use of the death penalty has a class bias and discriminates against powerless people in our society. The poorer a person is, the more likely he is to be sentenced to death in India.

The death penalty is also awarded in India in ways the Supreme Court has described as inconsistent, subjective and judge-centric. Convicts who commit similar crimes are given differing judgments: the death penalty by some judges and life imprisonment by others. The Supreme Court has pointed out that courts have made mistakes in using the ‘rarest-of-rare’ test to determine if the death sentence should be given. At least 13 people have been sentenced to death by the Supreme Court in judgements that did not apply the test correctly.

Death penalty does not make us safer. When politicians and religious leaders continue to make outrageously sexist statements, when police officials refuse to register or investigate cases and blame the victim instead, when judges are inconsistent and arbitrary in their rulings, it is naïve to think that death penalty is the silver bullet that ends violence against women.

As the Constitutional Court of South Africa said in 1995 when it abolished the death penalty, “We would be deluding ourselves if we were to believe that the execution of…a comparatively few people each year…will provide the solution to the unacceptably high rate of crime. … The greatest deterrent to crime is the likelihood that offenders will be apprehended, convicted and punished. It is that which is presently lacking in our criminal justice system; and it is at this level and through addressing the causes of crime that the State must seek to combat lawlessness.”

When a heinous crime occurs, public outcries for strong action and retribution are understandable responses. However, personal anger and grief should not be used to justify executions.

If the idea is to end violence in society, then killing is certainly not the answer.

December 19, 2013 at 8:50 am

Death Penalty or any other punishment, the underlying idea is to instil fear in the minds of potential offenders as well as to assuage the hurts caused to the victims and their kins. Have we succeeded to stop other crimes where death penalties are not warranted ? NO, we have not

This shows that punishments are more for assuage than for fear.. We should work more on improving mindsets that lead to reduction in crimes and on fining more humane ways of assuaging the hurts caused . Some sorts of compensations to the victims/kins, for example ?. And life term punishment with very hard labour.for heinous crimes like rape murder or instigating murder..

BSRawat .