The BJP candidate may be leading India‘s prime ministerial election polls, but his record, while good, doesn’t justify the hype Maitreesh Ghatak and Sanchari Roy

Thursday 13 March 2014

theguardian.com

—-

Narendra Modi, the prime ministerial candidate of the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) in the forthcoming Indian election, is leading the opinion polls right now. To his supporters he is an efficient, tough and incorruptible administrator whose style of economic governance – dubbed “Modinomics” – has worked wonders in Gujarat and can be rolled out across India. To his detractors he is a rightwing Hindu nationalist with autocratic tendencies, whose magic touch governance was strangely ineffective in containing the religious violence that broke out in 2002, and whose boasts of Gujarat’s economic success under his watch are belied by the uneven distribution of gains from growth and persistent poverty.

Leaving political issues aside, what does Gujarat’s economic record under Modi actually look like? Take the most obvious indicator, the growth rate of per capita income, supposedly a strong point of Modi’s economic scorecard. Many people are arguing that Gujarat has grown faster than the rest of India since Modi came to power in 2001, and present this as clinching evidence for the power of his economic model.

There are two problems with this argument. First, there are other states that have achieved this, but no one is talking about the Maharashtra or Haryana model of development. Second, Gujarat’s growth rate was higher than the all-India level in the 1980s and 1990s as well. To establish the claim that Modi had a transformative impact on the state in terms of growth rate of per capita income, we have to show that the difference between Gujarat’s growth rate and that of the rest of India actually increased under Modi’s rule, and more so compared to other states.

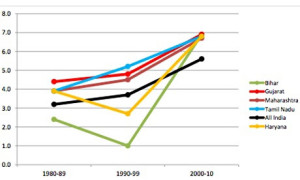

Gujarat’s growth rate in the 1990s was 4.8%, compared to the national average of 3.7%; in the 2000s it was 6.9% compared to the national average of 5.6%. The difference between Gujarat’s growth rate and the national average increased marginally, from 1.1 percentage points to 1.3 percentage points. A good performance? Yes. Justifying the hype? No. Maharashtra, the top-ranked state in terms of per capita income in the 2000s, improved its growth rate from 4.5% in the 1990s to 6.7% in the 2000s. The difference between Maharashtra’s growth rate and the national average grew from 0.8 percentage points to 1.1 percentage points. Contrast this with the performance of Bihar, the state that has been in the bottom of the rankings in terms of per capita income throughout: its growth rate was 2.7 percentage points below the national average in the 1990s, but 1.3 percentage points higher in the 2000s. So the prize for the most dramatic turnaround in the 2000s would go to Bihar.

IIAverage annual growth rate of per capita income of selected Indian states, by decadeAverage annual growth rate of per capita income of selected states, by decade

Note: Per capita income of a state implies net state domestic product of India.

Source: Reserve Bank of India

What about the other economic indicators? For the human development index, Kerala has been the star performer by a distance. While Gujarat’s HDI performance was above the national average in the 1980s and 1990s, it decelerated in the 2000s and came down to the national average. The level of inequality in Gujarat was less than the national average in the 1980s-90s, but actually rose above the national average in the 2000s.

If we look at the percentage of people below the poverty line, Gujarat, along with several other states such as Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Kerala, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, has had consistently lower levels than the all-India average. However, the largest poverty reduction of the past decade was achieved by Tamil Nadu, not Gujarat.

So while Gujarat’s overall economic record has been undoubtedly good over the past three decades, its recent performance does not seem to justify the wild euphoria and exuberant optimism about Modi’s economic leadership.

Though Modi’s stock is rising high, evidence for the success of Modinomics is unconvincing. For those frustrated with the status quo and hoping for a magical turnaround of the Indian economy if Modi comes to power, it may be wise to think about lessons from the stock market. At some point all bubbles burst – and the numbers have to add up.

• This is an edited extract of a forthcoming essay that will be available on Ideas for India from 22 March, where details of the statistical analysis, including data sources, tables and figures, will be presented.

Read more here — http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/mar/13/modinomics-narendra-modi-india-bjp

Leave a Reply